This past weekend I attended the Duke Advanced Vitreous Surgery Course in beautiful North Carolina. What a fun weekend to reconnect with other retina fellows from around the country and learn from an impressive array of retina faculty.

The meeting was a busy two-day collection of presentations and expert panels on everything from management of diabetic retinopathy and proliferative vitreoretinopathy to tips on the job search and work-life balance. The wet-lab was an interactive practice-lab to give retina fellows experience with advanced vitreoretinal surgery techniques, including administration of sub-retinal gene therapy, secondary intraocular lenses, intraoperative OCT, heads-up 3D surgery, and removal of perfluorooctane (PFO) under silicone oil.

Here are just a few (of many!) highlights from the meeting.

Age-Related Macular Degeneration.

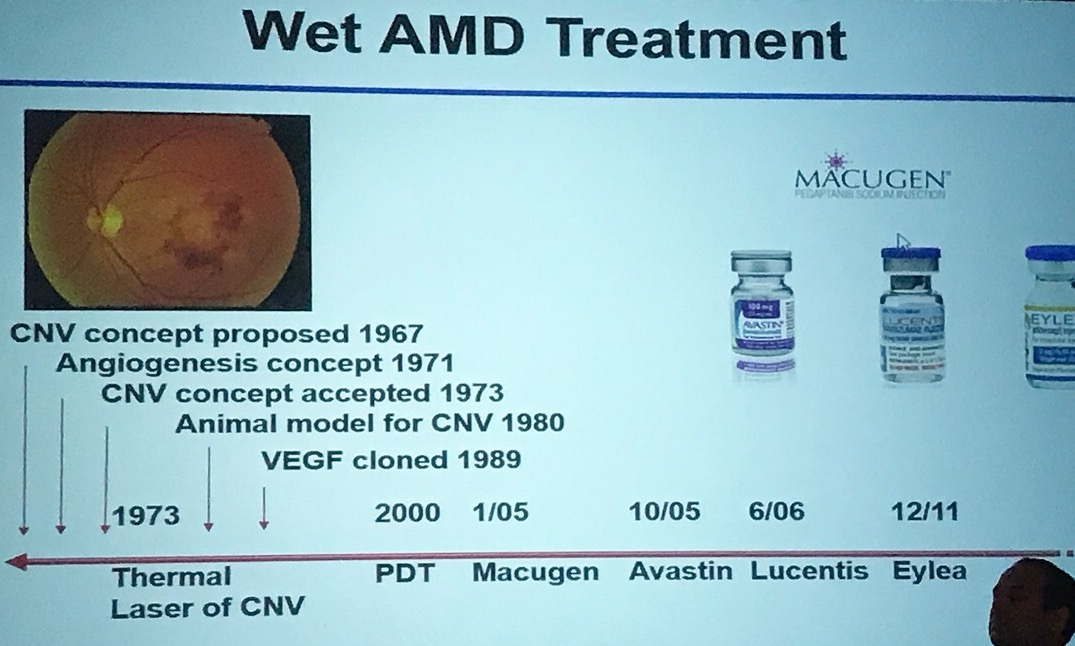

Several speakers referenced the history of treatment for wet age-related macular degeneration. Scott Cousins, MD showed a slide demonstrating that for us retina fellows today, we were truly born in the anti-VEGF era, as VEGF was first cloned in 1989 and Macugen was first used for wet AMD in 2005. George Williams, MD alluded to the “logarithmic” growth in intravitreal injection use, many of which are for the treatment of wet ARMD, explaining that in 2002 just 4,000 intravitreal injections were given, increasing by “two log units” to 4,000,000 in 2012. Many new drugs for use in non-neovascular and neovascular ARMD are currently in clinical trials, and as a retina fellow today, I wonder if I will one-day I will nostalgically remind the future retina fellows of the year 2075 that, “in the bad old days (today), we used to give anti-VEGF injections every four weeks!” I can’t wait to see the emergence of new drug targets and therapies in the coming years which will decrease the seemingly unsustainable injection burden and improve treatment of wet macular degeneration.

History of Wet AMD Treatment

Diabetic Retinopathy

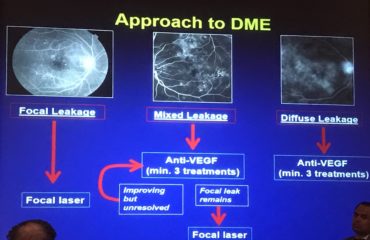

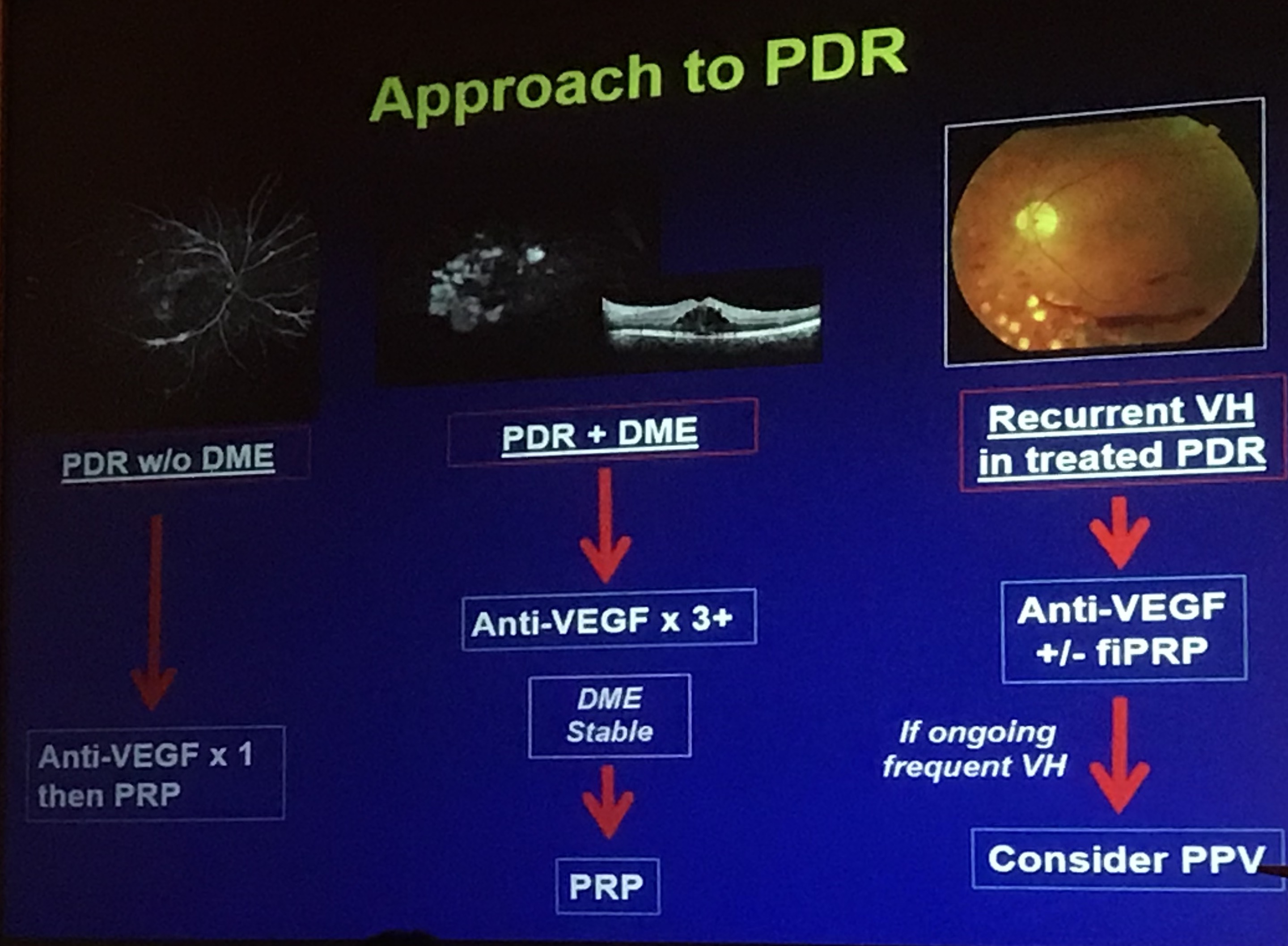

Michael Allingham, MD, PhD gave a fantastic talk highlighting his approach to treating diabetic retinopathy, and more specifically, the treatment of macular edema with/without proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Now nearing the end of my first year of fellowship, I have noticed that everyone has “their” approach to treating these incredibly common conditions, and it can, at times, be difficult to retrospectively try and decipher the management “approach” employed by any specific physician. Dr. Allingham’s two flowcharts depicting the “Duke approach” to treating PDR +/- DME help my constantly evolving approach to managing these challenging diseases. Later in the course, the incredibly-accomplished-but-refreshingly-honest David Brown, MD presented his investigator-driven “DAVE” trial, examining the use of panretinal photocoagulation for diabetic macular edema with peripheral non-perfusion, which showed no evidence that combination therapy with ranibizumab and targeted PRP improved visual outcomes or reduced treatment burden compared with ranibizumab alone, presumably related to the relatively lower oxygen demand of the peripheral retina (with fewer photoreceptors) compared to the higher metabolic/oxygen demand of the macula (with many more photoreceptors).

The Duke approach to DME

The Duke approach to PDR

Vitreoretinal Surgery

The surgically-relevant content was spot-on and perfectly tailored to the skill and knowledge of the first-year vitreoretinal surgery fellows in attendance.

Primary retinal detachment: what to do and what not to do

John Kitchens, MD gave his “Do’s and Don’ts” of retinal detachment repair. Here are just a few that made Kitchens’ list, with a bit of my own editorialized paraphrasing.

DO

Do what you are comfortable with – when you first start training, do things how you learned to do them in training. It will be tempting to do things like the other surgeons in the group, but stick with what you know, at least at first.

Do have a plan and a routine – run through the case in your mind the night before surgery, anticipating where you might run into problems and how you will manage each.

Do keep track of how you are doing – keeping a good surgical log can help you know how your surgical success-rates compare to benchmarks. Kitchens cited a 70% single operation success rate for pneumatic retinopexy, 80-85% for primary scleral buckle, 80% for primary vitrectomy, and over 90% for scleral buckle with vitrectomy.

Do try new things (after 6 months or so) – surgical instruments and techniques change rapidly, and you must learn new techniques to offer the best treatment for patients. Don’t try new things too soon, but after a few months, start implementing and learning other techniques into your own surgical practice.

Do document macular status. Always document whether the macula is attached/detached, and if there is a question, get an OCT. Show the OCT to the patient, especially in macula-off detachments, to help frame the discussion of anticipated post-op visual recovery.

Do communicate (in writing) with the referring doctor and the patient – Dr. Kitchens dictates a note to the referring doctor, immediately after the patient visit, and with the patient still sitting in the room. He finds this helps the patient hear, once again, the treatment plan, and helps build relationships with other providers. He also likes to send a copy of this letter to the patient for their own records. Later in the program, George Williams, MD, discussing how to avoid malpractice claims, advised fellows to always document in the operative note the rationale for the patient needing surgery.

DON’T

Don’t be afraid to ask for help. Ask a more senior partner to join you in surgery. This builds camaraderie, demonstrates humility, and shows you have a desire to learn and improve. Be careful not to handle super-challenging cases too early – refer these cases to a more senior partner until your skills improve and surgical confidence increases.

Don’t let a multifocal intraocular lens dissuade you from a scleral buckle – if cataract surgeons will treat post-phaco patients with an refractive surgical “enhancement,” they can (in many cases) similarly treat a post-buckle patient with refractive surgery for buckle-induced myopia.

Don’t be afraid to buckle thin sclera. Every preop RD-repair exam should include an examination of the sclera, looking carefully for thin sclera that can be reinforced with a scleral buckling procedure. If there is focal thinning or a staphyloma/ectasia, consider a larger buckle element in the area of concern.

Don’t be afraid to give your cell-phone number to patients. Dr. Kitchens shared his overall-positive with sharing his personal cell-number, stating that patients really appreciate the gesture, in most cases are careful not to call/text him unnecessarily, and that his resolving simple concerns via text (i.e. subconjunctival hemorrhage via shared cell-phone pic) allows him to address the concern even while out of town – and mitigating the need for his partners to deal with simple issues on his patients in his absence.

Don’t be afraid to use oil. Silicone oil can help in many situations, and while it requires an additional trip to the operating room, it is often necessary to optimize surgical outcomes.

Don’t succumb to denial. As soon as we encounter an unanticipated surgical event (whether or not iatrogenic), we often want to deny what we see and continue with the procedure. He advised fellows to not succumb to denial, but take the next steps to resolve the issue appropriately.

Pneumatic retinopexy – tips and tricks

Caroline Baumal, MD then gave a fantastic talk on the indications and surgical technique of pneumatic retinopexy for primary retinal detachment repair. She described the traditional pneumatic retinopexy candidate as a patient with a single break or >1 breaks within 1 clock hour of each other, with a retinal deteachment in the superior 8 clock hours (between 8 and 4 o’clock), with clear media, able to position, and without proliferative vitreoretinopathy, inferior breaks, large breaks >3 clock hours, a vitreous hemorrhage, or a giant retinal tear. She then explained her technique of obtaining a single intravitreal gas bubble, which includes reclining the patient and having them look up, with chin up in order to place the inferior pars plana at the highest anatomical position (remember that the RD is superior so thus the gas would be injected anterior to attached inferior retina), inject at six o’clock by entering with the needle, injecting a little bit, and then pulling the needle back (still in eye) to then inject the gas into the bubble created on the initial injection. Baumal believes that her pneumatic retinopexy success-rate increased when she improved her ability to obtain a single gas bubble. If multiple small bubbles result, she recommended placing the patient face down for several hours, allowing the bubbles to coalesce into a larger bubble, and then position as indicated. Baumal then outlined her overall technique for pneumatic retinopexy, as follows:

- Consent

- SC 2% Lidocaine (without epinephrine) at cryo site and gas site (6 o’clock)

- Lid speculum in, perform cryo, lid speculum out

- Draw up 100% SF6 gas

- Explain head positioning

- Lid speculum in and treat with betadine

- Position 1 – head flat – perform paracentesis to remove 0.1 (phakic) or more if pseudophakic

- Position 2 – chin up/look up – perform gas injection technique, roll over injection site with sterile q-tip

- Position 1 – paracentesis

- Betadine and wash off

- Roll on side, sit up, IOP check, ointment, patch, done

Managing PVR

Dean Eliott, MD discussed surgical management of proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR). He reviewed the historical use of retinectomy for PVR, stating that earlier studies reported retinectomy as being used in just 2-8% of cases with early PVR, increasing to 29% in 1993 and, more recently, up to 64% of vitrectomy cases with PVR. Retinectomy can be one of three types: inferior 180 degrees, 360 degrees, or in a focal area posteriorly. If doing a 180 degree inferior retinectomy, Eliott recommended surgeons create the retinectomy from 3 to 9 o’clock posterior to the vitreous base, followed by endodiathermy to prevent bleeding and delineate the retinectomy edge, followed then by laser. He counseled against use of a 270 degree retinectomy, and suggested extension to a complete 360 degrees instead.

Dr. Eliott described the four most common retinectomy mistakes: 1. Failure to peel all epiretinal membranes, 2. Failure to peel all subretinal membranes, 3. Failure to place a scleral buckle, and 4. retinectomy being made too small.

He also described the rationale for performing lensectomy in cases of PVR, including the ability to perform a more complete vitrectomy, giving access to anterior proliferations and the release of anterior retinal and ciliary body traction. Dr. Eliott recommended removing the anterior capsule, as he has seen multiple cases where the capsule was left intact with the thought of subsequent placement of a sulcus intraocular lens, only to have the capsule become opacified, development of posterior synechiae, and pupillary block resulting in iris bombe – all of which could have been avoided if the anterior capsule were also removed at the time of lensectomy. With regard to scleral buckles for PVR, Eliott stated that a buckle is not necessary if a 360 degree retinectomy or extensive anterior laser is performed. Finally, he gave several tips on using PFO or silicone oil, counseling attendees to mitigate against subretinal PFO migration by avoiding turbulence with a lower infusion pressure. He explained that in an aphakic or pseudophakic eye, he likes to use a 25 gauge needle on a TB syringe with the plunger-pulled as a chimney to vent the air while filling with silicone oil.

Private Equity in Ophthalmology

Gaurav Shah, MD gave two outstanding talks at the meeting, the first a primer on private equity in ophthalmology, and the second on contract negotiations. Shah’s talk on private equity was a fast-paced review on everything from the history of private equity in ophthalmology to practice valuation and an overview of how private equity may impact early-career, mid-career, and late-career ophthalmologists. He also gave a nice shout-out to an article posted here on private equity in ophthalmology which I hope has helped contribute to education about this topic amongst my ophthalmology colleagues.

Notable and quotable

Finally, there were MANY one-liners that were just too good not to share. Here are a few slightly paraphrased one-liners (or few-liners) that come to mind.

George Williams, MD

- Never let someone draw up a drug or dilute a gas (in surgery) without you watching to ensure they do so correctly.

- Modern cataract surgery is the best deal in medicine. It works 99 percent of the time and lasts a lifetime. All in all it costs the government about 3000 bucks.

- In the course of the day you’ll have really easy patients and really hard patients. The most important thing is to give each the time they need. There will be the intravitreal injection that takes very little time, and you can pick up a few minutes by completing that encounter quickly, and then later in the day there will be a challenging patient that will take more time. Be smart with this.

- Try not to overschedule yourself. Avoid situations such as trying to fit in one more case before you need to rush out and catch a flight.

Gaurav Shah, MD

- Time is the most precious commodity. It’s not about money. It’s about time.

John Kitchens, MD

- The only surgery you’ll never regret is the one you don’t do.

- Fix the bad eye before trying to fix the good eye.

Conclusion

What a fantastic meeting. Thank you to Lejla Vajzovic, MD and the other faculty and administrators of the Duke Eye Center for planning and hosting the event, to the industry sponsors for their financial support which made it all possible, to the all-star teaching faculty who spent a weekend away from friends/family/fun to be with us, and to the awesome group of my co-fellows from around the country who arranged call/vacation/work schedules to be in attendance.

Planned photobombed selfie of friends and retina fellows from around the country.